The Impact of Covid-19 on Working Practices and Office Demand

Homeworking trends since Covid-19

Anecdotal evidence on homeworking trends generally concurs that a rise in remote working in typically office using sectors has a proportionately high negative impact on demand for office space. However, there is insufficient empirical evidence at this stage to help quantify the reduction in demand as a result of homeworking.

The ONS conducted a study of regional patterns of homeworking in the UK[1] between the most recent period of data available and the period prior to the introduction of guidance and legal requirements to work from home[2].

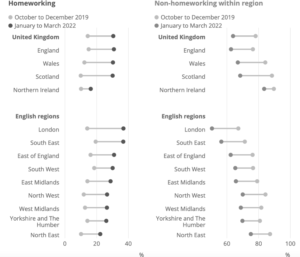

The study found that between Q4 of 2019 and Q1 of 2022, homeworking in the UK more than doubled from 14.5% (4.7 million) to 30.6% (9.9 million). Regional variations were also observed, with London and the South East seeing the largest changes in homeworking and non-homeworking. However, all regions across the UK saw significant increases in homeworking and decreases in non- homeworking.

Figure 1: Change in homeworking and non-homeworking, October to December 2019 and January to March 2022, UK regions, not seasonally adjusted

Source: ONS Homeworking in the UK – regional patterns: 2019 to 2022

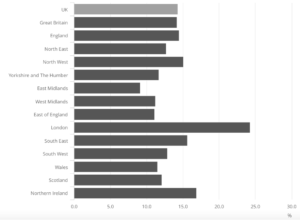

The study also found a 14% increase in flexible working[3]. Again, there were regional variations in flexible working increases, with London, the South East and the North West experiencing the greatest increase and East Midlands, West Midlands, and Wales seeing the lowest increase.

Figure 2: Percentage of workers who do not mainly work from home (non-homeworkers) but reported working from home at least one day in the reference week, January to March 2022, UK regions

Source: ONS Homeworking in the UK – regional patterns: 2019 to 2022

How these figures translate to office usage varies by study. Consultancy firm Advanced Workplace Associates[4] reported that UK average office attendance was 1.4 days, compared with 3.8 days pre Covid-19. The study, which used a survey population of 77,410 across 28 organisations, also found that average desk usage in the UK was 33% across the week. This varied throughout the week, with Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday experiencing average desk usage of 40%, whilst desk usage on Monday and Friday was lower at 24% and 16%, respectively.

Whilst the implications for office demand should not be understated, any changes which do take place will be slowed down by the duration with which businesses are locked-in to their office leases, which can often run for ten years or even longer and with expensive termination fees. In addition, many businesses are yet to decide which working practices best help to achieve business goals, which will further hinder any changes to demand. This means only those firms with upcoming lease renewals, or break clauses or those that have decided which working practices can work best will be able to implement office reduction quickly.

Looking further into the future, if remote working begins to drive down the demand for office space and, in turn, office rents, there is the potential that new occupiers- particularly those that had previously been priced out from renting office space – will take up the opportunity of renting an office space. This may then result in a maintained quantity of demand which existed prior to the remote working exodus. However, this will depend on the commercial viability of landlords maintaining offices at lower rents and whether the building can be repurposed to meet other needs. The redevelopment of offices into houses to meet the housing shortage has been touted as a possible long-term effect, one which may exacerbate the prevailing trend of converting offices to residential uses as a result of permitted development rights. .

The impact of remote working on employment densities

An emerging question which is linked to the scale and impact of homeworking surrounds changing office floorspace density. According to Deloitte[5], most developers in London argue that the reduction in office occupation due to remote working is likely to be offset by growing requirements of tenants for lower density occupation, less hot desking and more collaborative space. These findings are replicated in a regional Deloitte survey indicating that the trend of lower density office occupation and retention of total floorspace demand will be reflected nationwide[6].

While some sectors may see a decline in the number of workers in the office at any given time, the amount of office space required is expected to remain the same, in order to facilitate group-meetings and collaboration when workers are in the office. Workers want a reason to come to the office if they are to commute, and heightened collaboration is one justification. While offices may become less occupied on a day-to-day basis, total floorspace requirements may remain the same.

One important caveat however is that if offices are becoming less dense, this is will not change uniformly across the office market. The amount of floorspace required by each worker will vary according to occupation, sector, business culture and business size.

The trend of lowering densities is also unbalanced with regard to high and low-value office space. While high-value businesses will continue to demand office space to support their corporate brand and images, it is uncertain whether the same level of investment will be placed into lower-grade office spaces with lower rents and where smaller grid sizes make it difficult to renovate. According to the Financial Times, it is likely many of these will ‘empty out and have to be refitted or repurposed’[7].

Finally, for remote working to lead to a lowering of density and a concurrent maintenance of space it will need to make financial sense for occupiers. The last 25 years has seen offices becoming denser in order to make them more economically viable[8]. For remote working to reverse this trend, and for offices to maintain high levels of space despite fewer workers in the office on a day-to-day basis, it will need to be financially viable for businesses. If it is not, lower density occupation may become a luxury not available to all and businesses may prefer to downsize, while maintaining some form of collaboration space.

The impact on location of new builds

The impact of home and remote working is also impacting the conversation around where we are likely to see new office spaces being developed. An emerging model of office development is that of the ‘hub and spoke’ system, whereby businesses retain a city centre presence (i.e. the hub), while also utilising regional and local office ‘spokes’, which could include out-of-town co-working workspaces.[5] The model has been promoted by Deloitte and KPMG and has received some media attention.[9]

This model is also likely to benefit from being more environmentally-friendly and compatible with the political and cultural shift toward a decarbonised economy. The hub and spokes model of office space will reduce the amount of travel required to a central location by bringing offices closer to the places where people live thereby reducing pollution.

Conclusions

As Covid-19 restrictions were lifted throughout the first half of 2022, emerging evidence has found that the greatest effects of remote working are being felt within the office sector. However, the scale of such changes remains uncertain. Whilst increased home and hybrid working is anticipated to stay, the effects of this could be offset by changes in occupation density. There may be spatial effects with a move to hub and spoke models, which also aligns to the Net Zero agenda. However, key factors of financial viability and lease flexibility will be critical to the speed at which any adaptations take place.

It will be important to monitor activity, particularly in the office sector, over the coming months and years to understand the medium- and long-term impacts on the demand for sites and premises.

[1] ONS (2022). Homeworking in the UK – regional patterns: 2019 to 2022- https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/homeworkingintheukregionalpatterns/2019to2022

[2] Using Labour Force Survey data, the study defines homeworkers as those who report either their own home, the same grounds/building or different places using home as a base as their main place of work. Non-homeworkers are defined as those who mainly worked somewhere separate from home.

[3] Flexible working is a measure of those who reported that they do not mainly work from home (non-homeworkers) working from home at least one full day per week. This helps capture those who work from home in some capacity.

[4] AWA (2022) Hybrid Working Index. https://www.advanced-workplace.com/the-awa-hybrid-working-index/

[5] Deloitte (2021) London Office Crane Survey https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/real-estate/articles/london-crane-survey-summer-2021.html/# https://research.bco.org.uk/resources/clients/3/user/resource_1023.pdf

[6] Deloitte (2021) Regional Crane Surveys https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/real-estate/articles/regional-crane-surveys.html

[7] Financial Times (2021) https://www.ft.com/content/d6b8d468-e339-497d-b165-0de10bcddcae

[8] British Council for Offices https://www.bco.org.uk/Research/Publications/Theme/working-practices.aspx

[9] Fast Company https://www.fastcompany.com/90545418/see-the-unusual-new-office-design-that-deloitte-and-kpmg-are-exploring

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]